GREG WILSON'S DISCOTHEQUE ARCHIVES #15

A guide to dance music's pre-rave past...

We've drafted in Greg Wilson, the former electro-funk pioneer, nowadays a leading figure in the global disco/re-edits movement and respected commentator on dance music and popular culture, to bring us four random nuggets of history; highlighting a classic DJ, label, venue and record each month.

A crucial, sometimes controversial force within Northern soul, Ian Levine probably unearthed more rare records than any other DJ during the scene’s ‘70s heyday.

Born in Blackpool in 1953, Levine started collecting Tamla Motown records in his early teens, and during trips to the US with his wealthy parents he was able to quench his obsession, bringing thousands of 7” soul singles, sourced in shops and warehouses, back home.

Exposed to Manchester Twisted Wheel DJs Rob Bellars, Brian Phillips, Stuart Bremner and Les Cokell, Levine caught this pivotal venue’s final flourish before its 1971 closure. Bringing in records for plays there, his reputation as a formidable collector was acquired well before he became a DJ.

With the Wheel gone, Blackpool Mecca, with Les Cokell and Tony Jebb DJing, grew in stature – contributions from Levine’s record collection a key factor. It was only a matter of time before he would take to the turntables himself.

All-nighter appearances at Stoke’s Golden Torch, which took up the baton from the Wheel, brought him into contact with Colin Curtis, and in 1973 the two began their hugely influential five-year Mecca Highland Room Saturday night partnership.

Alongside the movement defining ‘60s 45s, Levine and Curtis would increasingly feature contemporary releases, both ‘modern soul’ and eventually disco, creating a bitter schism with Wigan Casino, the scene’s leading venue (where Levine had previously guested), which opened at 2am just as, 40 miles away, the Mecca closed – the Casino’s traditional approach at odds with the Mecca’s progressiveness, Levine and Curtis regarded as heretics.

Not content just playing records, Levine would produce his own, including UK hits for The Exciters, L.J. Johnson and Evelyn Thomas. He was the first British DJ to produce dance tracks – Barbara Pennington’s ‘Twenty-Four Hours A Day’, a major New York disco cut in 1977.

Visiting NYC’s gay clubs during the mid-‘70s, Levine came to appreciate the evolving disco movement, and this was his direction of choice having left the Mecca in 1978, helping pioneer mixing in this country at Angels in Burnley.

Moving to London in ‘79, he became resident at new gay megaclub, Heaven, on the recommendation of US DJ Greg James, who’d introduced mixing to the UK via his late ‘70s residency at The Embassy in London.

Championing hi-NRG, both with regards to what he played and produced, including major hits for Miquel Brown and Evelyn Thomas, Levine remained at Heaven throughout most of the ‘80s.

With little interest in the burgeoning house/rave scene, he moved in a more mainstream direction during the ‘90s, producing tracks for boy bands Take That and Bad Boys Inc amongst others.

Set up in New York by Ahmet Ertegün, son of a former Turkish ambassador to the US, with partner Herb Abramson, Atlantic struggled over its first few years, but fortunes changed when the focus shifted from modern jazz to rhythm & blues – their breakthrough courtesy of Stick McGhee’s 1949 R&B hit ‘Drinking Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee’.

The label came into its own during the ‘50s, Ruth Brown scoring a quartet of R&B #1s between 1950-54, including '52’s ‘(Mama) She Treats Your Daughter Mean’, which also went top 30 pop. However, their greatest acquisition wasn’t an artist, but producer/A&R man Jerry Wexler, who joined the company as a partner in 1953.

Wexler was a music journalist who’d actually coined the term rhythm & blues as a Billboard magazine chart category for contemporary black music (previously listed under the heading ‘Harlem Hit Parade’). Throughout the ‘50s Wexler would take to the studio with artists including Ray Charles, The Drifters, LaVern Baker and Big Joe Turner, helping turn Atlantic from a small independent into a major chart force capable of million-selling hits.

Atlantic’s first major crossover was ‘Sh-Boom’ by The Chords in 1954, the first doo-wop track to go top five, whilst pop/rock & roll subsidiary Atco would score big later in the decade through The Coasters and Bobby Darin. Songwriters/producers Leiber & Stoller greatly enhanced their legacy working with the label’s artists, whilst Phil Spector cut his teeth there as a staff producer before unleashing his hit-laded Wall Of Sound.

In 1959 Ray Charles’ seminal soul single, ‘What’d I Say’, the labels best-selling song to date, ushered in a new era, with Atlantic/Atco right at the cusp of things - ex-Drifter Ben E. King setting the tone for the decade ahead with classic singles ‘Spanish Harlem’ (1960) and ‘Stand By Me’ (1961), his ex-group continuing their own run of hits despite his absence.

Their licensing deal with Memphis independent Stax Records brought aboard Otis Redding, Sam & Dave and Booker T. & The M.G.’s, now regarded as all-time soul greats, as were Atlantic signings Wilson Pickett, Percy Sledge and ‘Queen Of Soul’, Aretha Franklin (the pop/rock roster also flourishing thanks to the likes of Sonny & Cher, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and Led Zeppelin).

Only Motown could boast more dancefloor favourites than the Atlantic/Stax axis. Having established itself as a trusted soul/dance music source, a key mod imprint from a UK perspective, throughout the ‘70s into the early ‘80s Atlantic continually unleashed soul, funk and disco favourites by The Spinners, Average White Band, The Trammps, Chic, Sister Sledge, Cerrone and Change, to name but a few.

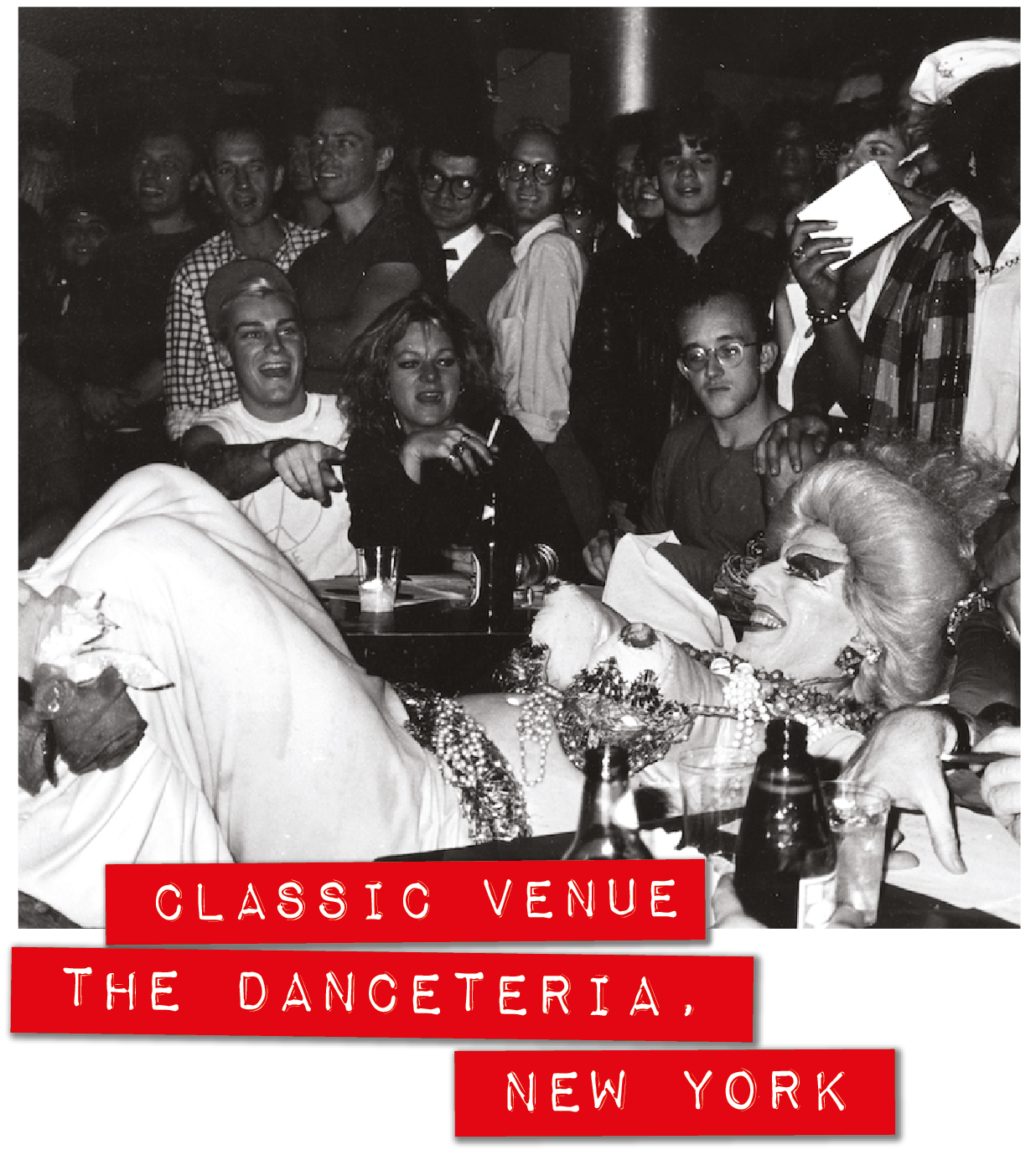

Of all the New York venues of the fertile early ‘80s, Danceteria best embodied the spirit of cross-pollinating creativity - its sensory overload spread throughout three floors.

Entrepreneurial German expat Rudolf Pieper and noted gay activist Jim Fouratt, having previously attempted to open the ill-fated Pravda club, which immediately closed following first night complaints from neighbours, acquired a midtown Manhattan venue soon afterwards and set about creating an immersive space they named Danceteria, complete with ironic ‘50s furnishing and walls covered in xerox art by a then up-and-coming Keith Haring – the audience a collision of art, fashion and music. The basement hosted DJs, the ground floor live bands and the first floor experimental film and pre-MTV music videos – offering revelers a multitude of options at once.

The club launched in May 1980, DJs Sean Cassette and Mark Kamins playing back-to-back for 12 hours. Cassette had previously been at punk haunt Hurrah with Kamins coming from rock club Trax. Alternating every few records, the partnership worked well, with Cassette’s punk and dub reggae leanings complemented by Kamins’ lateral approach to disco.

Operating without a license, Danceteria survived less than a year, with Kamins and Cassette moving on to CBGB. Kamins returned to the second Danceteria, opened in 1982, he’d have the decks to himself three nights a week in the basement and began experimenting with mixing, taking in the new emerging electro sounds, whilst Mudd Club DJ Anita Sarko played between bands on the ground floor and early VJs experimented with music videos and found footage on the first floor.

The club’s staff and clientele included a number of people who’d later become well-known; Sade was a bartender, Keith Haring and The Beastie Boys were busboys and LL Cool J worked as an elevator attendant. Madonna, the then girlfriend of Kamins, first performed at Danceteria, before rising to global fame – the DJ helping her land a record deal with Sire, producing her first single ‘Everybody’ (1982).

The club was a key influence on Manchester’s Haçienda and in 1984 Kamins was the first US DJ booked to play there. Danceteria mk2 closed in 1986, Kamins going on to pursue a career in production whilst picking up DJ bookings in countries like Japan and Italy. A third Danceteria opened between 1990-93, but it would never live up to its much-loved second home.

In 1976, with the disco era having hit its stride, New York magazine published an article by British rock journalist Nik Cohn, best-known for his pop history ‘Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom’ (1970). The article, ‘Tribal Rites Of The New Saturday Night’, outlined this flourishing culture of the after-dark. He would later reveal it as a complete fabrication, resulting from conversations with clubgoers in England – its central character based upon a ‘60s mod he’d known.

The piece revolved around a real discotheque, Brooklyn’s 2001 Odyssey and the nocturnal exploits of dance floor hero, Italian-American, Tony Manero.

Expanding into film production via 1973’s adaptation of the stage musical ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’, Australian-born impresario Robert Stigwood, who’d found success back in the ‘60s managing artists including Cream and the Bee Gees, would also bring The Who’s ‘rock opera’ ‘Tommy’ to the big screen in 1975. His third film, based on Cohn’s article, would be 1977’s ‘Saturday Night Fever’, a huge commercial success that would popularize disco music worldwide, casting a young actor called John Travolta as Monero.

The film’s soundtrack would be a phenomenon in its own right - the best-selling LP of all-time until Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’ overtook it five years on. A 17 track double-album, dominated by the Bee Gees, who, after a fallow period in the early ‘70s, had re-invented themselves as a disco force. New recordings, ‘Night Fever’ and ‘Staying Alive’ would become US #1s, whilst previous chart toppers ‘Jive Talkin’’ (1975) and ‘You Should Be Dancing’ (1976) also featured. The 1977 ballad, ‘How Deep Is Your Love’, made it a handful of #1 inclusions for the Bee Gees.

The soundtrack also featured Yvonne Elliman, Walter Murphy, Tavares, David Shire, Ralph MacDonald, Kool & The Gang, K.C. & The Sunshine Band, MFSB and The Trammps, whose classic ‘Disco Inferno’ was revived for one of Monero’s dance sequences, utilizing the Puerto Rican originated ‘hustle’ style, which had caught on with the wider NYC disco community.

Whilst the film, and the culture it highlighted, was initially acclaimed, it set in motion the backlash that would manifest so devastatingly for the disco industry via 1979’s ‘Disco Sucks’ movement.

It would also, in certain respects, whitewash disco music’s roots with its iconic figure of the white Monero character in a white suit, one arm held aloft, usurping the afro-haired black dancer as the image most associated with disco. In a similar manner the Isle of Man born and Manchester/Australia raised Bee Gees would embody the movement for a whole new swathe of disco enthusiasts, disconnecting the music from its underground foundations in the black and gay communities.

Written by Greg Wilson

Edited by Josh Ray

'Mr. Levine' illustration by Pete Fowler

Check out the previous Discotheque Archives here